Post-War

After the war, on July 30th, 1946, camp Commandant Amon Goth was put on trial after being arrested by the US government and turned over to Polish authority (n.d. 107). Amon Goeth went on trial for his brutal crimes at the Plaszow camp and his part in the genocide of Polish Jews (Bazyler & Tuerkheimer, 101). He was charged with a total of 5 counts surrounding the deaths of 8,000 Jews: one count of killing Jewish prisoners with beatings, torture, or being savaged by dogs, a second count for the “final liquidation” of the Krakow ghetto, a third count for the liquidation of the Tarnow ghetto where Goeth participated in the killing, beating, and tormenting of ghetto inhabitants, a fourth count for the liquidation of the Szebnie labor camp, and a fifth count for stealing money and items from the victims (Bazyler & Tuerkheimer, 116). This included stealing from Jews and keeping the profits, killing his Jewish prisoner/personal assistant who helped Goeth put his stolen goods on the black market, and killing his immediate family members and other Jewish assistants. Amon Goeth’s main defense was that “any death sentence that was carried out was done so with the knowledge and authorization of his superiors” (125). Nevertheless, Goeth was found guilty on all counts because “there was no justification under the law of war for the liquidation of defenseless civilians” (125). On September 13, 1946, Amon Goeth was privately hanged to death on the grounds of the Plaszow labor camp (125).

Many freed Jewish prisoners saw Jewish policemen as being a part of a criminal organization worthy of punishment for serving as “accomplices to crimes committed in the ghetto and camp (Jarkowska-Natkaniec, 159). When it came to the fate of the Jewish police, also known as the OD and Judenrat, who were in charge of running much of the Plaszow camp in conjunction with SS soldiers, many of them stood trial before the Special Criminal Court in Krakow from 1945 to 1947 and were persecuted under Polish law (Jarkowska-Natkaniec, 156). The majority of Jewish police officers were not convicted, because they either died in December of 1943 at Plaszow, or emigrated once the war was over (159). A total of 40 Jews accused of collaborating with the Nazis were put on trial. 30 were sentenced, and two among them, doctor Leon Gross and “OD-man” Majer Kerner, “were sentenced to death for collaborating with the Nazis” (Jarkowska-Natkaniec, 157). Kerner was in charge of most of the administrative duties at the camp, maintained the order of the barracks and assembly ground, and displayed “sadistic abuse of other prisoners at Plaszow” (158). Overall, Jewish policemen and collaborators were left unpunished.

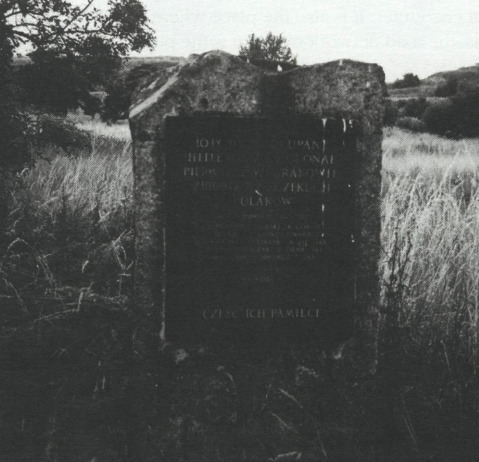

In the aftermath of the Plaszow camp and the Holocaust, it has been difficult “to maintain the site’s sacristy amid an increasingly distractive urban landscape”, and Schindler's List has only contributed to this dilemma (Drozdzewski 255). “While Plaszow is specifically designated a site of national commemoration, the paucity of ritual or purposeful markers of commemoration there relate to how the site intersects with and shares the urban landscape that surrounds it” (256). The “site’s sacristy is increasingly out of step with its surrounding environment”. During the war, the Plaszow camp was constructed on top of two Jewish cemeteries, and expanded as the Krakow ghetto was liquidated. A key aspect that differentiates Plaszow from other memorialized concentration camps is that it doesn’t have any “material markers” of its past. Before the 1944 evacuation of the camp, the Nazi administration destroyed any incriminating markers of what happened at the camp, including barracks, parts of the barbed wire fence, crematoria, and as many buildings as possible (256). Much of the area that previously served barracks, is now a site of vegetation. In contrast to other camps that now serve as tourist sites where people can explore the history and be led to certain attributes of the camp, Plaszow “is largely an untended and unmarked green space”. There aren’t any maps, signs, plaques, or pictures (256). Plaszow seems to memorialize the absence and vacancy that the Nazi army sought to bring about, instead of the victims and over 9,000 individuals that were executed and buried at Plaszow (257). Drozdzewski explains that the absence that is currently integrated into the Plaszow site may not be entirely without thought; Visitors to the site are meant to rely on their “empathetic insiderness” and aid in the remembrance of what occurred at Plaszow. The memory of Plaszow is therefore driven through external forces, i.e. visitors unknown to the camp, rather than the internal written and oral history that is often seen in Holocaust museums and sites today.

But much of the camp is still unregulated. Parts of the grassed area are used for ball games by adults and children, picnics, walking dogs, an adventure playground, etc. There is a juxtaposition between the national and international obligation to remember the atrocities that occurred and “those that must continue a daily existence in the environments where the atrocities occurred” (260).

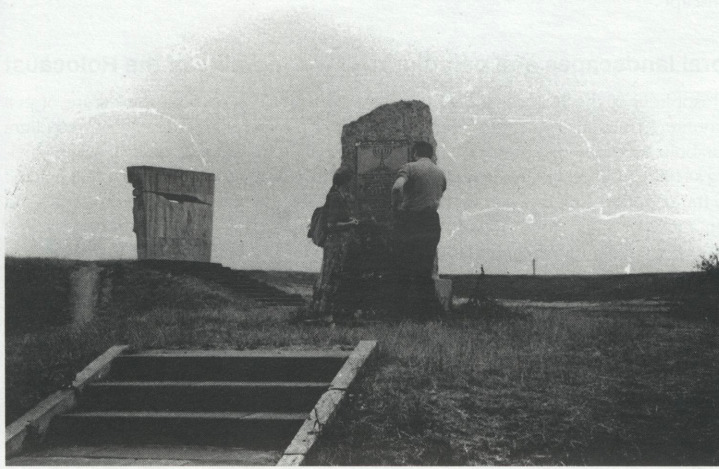

Four monuments are in place at Plaszow: a large post-Socialist monument, two Jewish monuments, one commemorating the victims of the camp and the other commemorating Hungarian Jews transported to the camp, and an additional monument for the Polish victims of the camp (260). But in a growing city, the open fields of the Plaszow camp landscape is under pressure from the surrounding city as the urban life commands more and more recreation space and land development, leaving Plaszow as one of the few sites that can serve as a recreation area for locals. The absence of commemoration at Plaszow, besides the four monuments, may leave it “virtually impossible to pass on memories from one generation to another” (262).

But Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List seemed to have an effect on the passive landscape of Plaszow’s memorial. In a post-Schindler’s List encounter of the Plaszow landscape, Andrew Charlesworth reviews and acknowledges that many more visitors and scholars frequent the camp and have a different expectation of the camp than pre-Schindler’s List visitors (Charlesworth, 296). They rely on pop culture for how they should remember the Holocaust and expect Spielberg’s vision to come to life when they visit the Plaszow memorial. This may further the good versus evil stigma that Schindler’s List produced, instead of focusing on the complexities and vast death that was involved in the Holocaust. But it made the Plaszow camp go from “global anonymity” to being infamous.